The Face of the Nation: Gendered Institutions in International Affairs

Posted on

International affairs is undergoing fundamental and rapid gendered change, spurred on by shifting social and governance norms and the adoption of explicit feminist foreign policies in some states.

In some cases, this has resulted in women’s increasing representation at the frontlines of global governance. Yet, progress is marred by women’s continued entrenched underrepresentation in leadership and experiences of challenges that have in cases increased, not decreased, in recent years.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and against a background of cascading crises, a rise in right-wing misogyny and anti-women’s-rights backlash, and archaic institutions moving at a glacial pace, women remain frequently sidelined, marginalised, undervalued, and overlooked in international affairs. Despite some progress, international affairs has a gender problem, and remains one of the worst-performing sectors of the state.

Australia is a global leader in terms of representation of women and policy supports for gender equality in governance. Yet Australia also demonstrates how deeply gendered, racialized, and heteronormative international institutions remain.

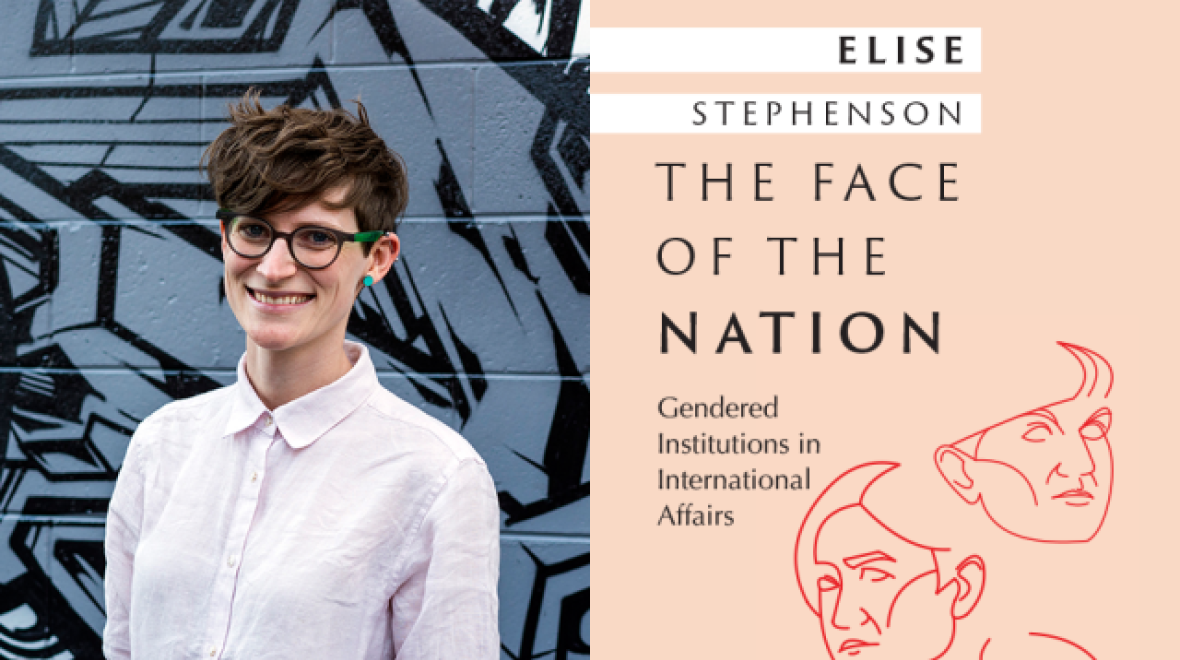

GIWL Deputy Director, Dr Elise Stephenson, studied women’s leadership and gender relations in Australia over the last 30+ years, spanning across diplomacy, defence, national security, policing, and intelligence to understand the disconnect between pockets of progress and undercurrents of resistance.

Her new award-winning book The Face of the Nation, unpacks this research and features in-depth interviews with almost 80 global leaders, including with Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Gillard, and first female foreign minister, Julie Bishop, to trace the evolution of inequalities in international affairs and interrogate why women still remain underrepresented in this field.

This research finds that...

- Women face a diplomatic glass cliff: Women are often elected to diplomatic leadership positions at a time when the diplomatic institution is shrinking in power and funding

- Military fields have better gender representation than diplomatic ones: With a level of transparency over career progression and the gendered nature of work contributing to this finding

- Diplomatic agencies can demonstrate 'genteel toxic masculinity': This is just as pervasive as more traditional forms of 'toxic masculinity', but harder to identify given diplomatic norms of gentility

- Queer women with wives often fit the "traditional" model of an ambassador than their heterosexual counterparts, but they face exclusion and discrimination: Women with wives (e.g. queer women) may be better equipped to fit the traditional model of (male) ambassador and (trailing) wife than their heterosexual counterparts: Despite this, they also face pervasive exclusion within the international system, with even 'straight' (but single) women sometimes typified as queer within the system, highlighting the co-constitutive effects of queer and gendered exclusion

- Women report more sexism and discriminiation in their home countries than in overseas postings: Whilst women's historical exclusion from diplomacy has often been premised based on their perceived negative treatment in 'foreign' countries, women reported greater instances of sexism and discrimination from their home, domestic institutions

- As diplomatic institutions evolve, so do inequalities.

The Face of the Nation was published in January 2024 and is available to purchase here or read an excerpt online here. You can find out more about the book, and learn more about Elise's research, here.