Is your workplace gender equality initiative actually effective?

By: Elise Stephenson, Gosia Mikolajczak, Michelle Ryan, Victor Sojo, Alexandra Fisher, Jack Hayes, Morgan Weaving and Mai Tanjitpiyanon

Posted on

As we head towards another International Women's Day, many organisations will turn their attention to gender equality in their workplace and consider launching a new women's empowerment or female leadership program in attempts to boost equality.

In fact, in recent years we've seen huge growth in the diversity and inclusion landscape, with a significant amount of effort and considerable resources being invested into leadership initiatives and gender equality programs. But is this investment paying off?

Many WLPs focus on equipping women with individual skills, confidence and access to networks, based on the evidence that women often lack opportunities to gain crucial leadership skills and connections and, underestimate their abilities. While improving opportunities for individual women is important, there is little evidence that WLPs tackle more systemic factors such as gendered norms and policies limiting women’s career progression. For this reason, WLPs have been criticised for their disproportionate focus on ‘fixing women’ (i.e., addressing individual barriers and skill ‘deficits’), which is relatively easy to achieve, instead of focusing on ‘fixing the system’ (i.e., addressing the systemic or cultural barriers), which is arguably harder to achieve but more important in helping women pursue and thrive in leadership roles.

As such, the increase in WLPs has been paralleled by a growing demand from organisations to understand not only how WLPs impact on individuals, but whether – and how – WLPs can make positive changes for organisations, communities, and gender equality more broadly.

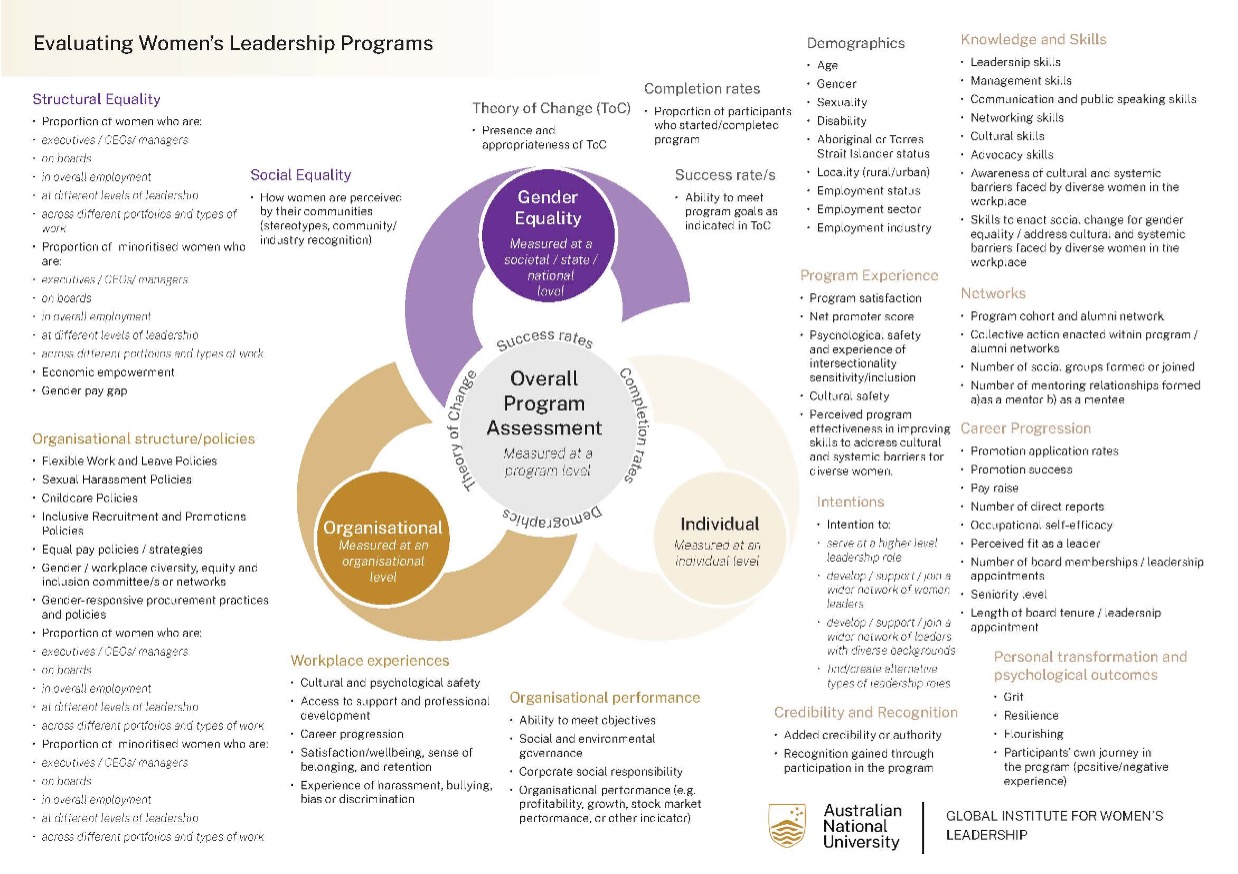

We’ve created a framework (shown above) and accompanying guide to help program designers and coordinators assess if their initiatives are actually working to advance gender equality – The GIWL Women’s Leadership Program (WLP) Evaluation Framework. The Framework assesses program impacts at the individual, organisational and structural level. We know that to make meaningful progress on gender equality, it’s not about “fixing” individual women to make them “more confident” leaders, but rather about addressing systemic issues at every level. So we made sure that the Framework evaluates the effectives of programs in addressing barriers to equality at every level – structural, organisational, and individual – to ensure that programs are achieving meaningful change and not just virtue signalling. The Framework takes an evidence-based approach, using the research on what works to advance equality.

Through our research, we found that various factors at each level challenge women’s advancement towards leadership positions. At an individual level, factors such as caring responsibilities, self-efficacy beliefs and confidence each affect women’s choice to apply for leadership roles. Organisational challenges often relate to masculine work culture, gendered workplace norms and exclusionary networks which may be critical for advancement into leadership positions. Structurally, these are things like stereotypes and pervasive gender biases in leadership positions. Factors from different levels are also interconnected, for example masculine leadership norms and stereotypes that associate leaders with men may bias the recruitment process in favour of men, leading to an overrepresentation of men in leadership and discouraging other women from applying for those positions.

To break these entrenched barriers, any WLP developed should aim to make impacts on individuals, organisations, and structural gender equality. The Evaluation Framework developed by GIWL ANU aims to measure the impact of WLPs over these three critical levels.

- At an individual level, we advise assessing program experience (e.g. satisfaction with program, willingness to refer it to others), knowledge and skills, behavioural intentions (e.g. do participants seek opportunities crucial to their development as leaders), networks (e.g. women often have more limited leadership social connections compared to men), credibility (e.g. whether participation enhances perceived credibility as a leader), personal transformation and psychological outcomes (e.g. perseverance), career progression (e.g. did the program result in promotion application/success, salary improvements, more direct reports, etc.).

- At an organisational level, we advise looking for changes in organisational structure and policies (e.g. recruitment, training, promotion, pay, performance evaluation, leave conditions, termination), organisational performance (e.g. profitability, growth, stock market performance), and workplace experiences (e.g. gender bias, discrimination, sense of cultural safety).

- At a structural level, we advise looking for changes in terms of structural equality (e.g. proportion of women in formal leadership positions, across different portfolios and types of work, etc.) and social equality (e.g. women’s experiences in leadership and how they are perceived in leadership at a broad level).

We also advise evaluating the overall project (for instance, in terms of success/completion rates and whether the program has a theory of change that links the initiative to overarching program goals, and outlines a path to get there).

While we have aimed to provide a detailed evaluation framework across structural, organisational and individual levels, we advise those charged with conducting the evaluation assess the program’s most critical indicators, and tweak as required. These indicators should be clear and identifiable when referring to a program’s theory of change.

The methodology chosen to evaluate a WLP should be tailored as per the program requirements, and may rely on pre- and post-survey data, as well as longitudinal survey data at a later date (e.g. 6 months, 1 year, 5 years). Additionally, interviews or focus groups with participants and other key stakeholders, as well as analysis of wider-standing data at national, state or organisational levels may help to triangulate data to determine WLP impacts.

We also advise considering the following three aspects that contribute to rigorous evaluation:

- A theory of change (ToC): A ToC allows organisations to get to the root cause of the issue they are aiming to address and map how their chosen policy program (like WLP) aims to influence or change that root cause. Once a WLP’s key components have been identified and its theorised causal pathways mapped and articulated, decisions can be made about which components and pathways of the program are of most interest to evaluate.

- A timeline for evaluation: If impact is assessed almost immediately or too late after the finalisation of the program, stakeholders may not link the achieved effects to the program itself. Moreover, longitudinal analysis may be needed to understand any medium to long-term impacts.

- Causality: To establish causality, it is firstly important to establish baseline data – the conditions or status of individuals, organisations and structures pre- intervention. In a best-case scenario, WLPs could also incorporate a control condition, with randomly assigned participants, (that is, a group of similar participants who do not receive the leadership training) to establish that any positive changes among participants in the leadership program were not found among participants in the control condition and were thus due to the leadership program specifically.

Ultimately, we argue that attention at design and delivery stages must be matched with attention at evaluation stages for WLPs to be most successful. Having dedicated theories of change would enable organisations to maximise the role that WLPs play in the broader context of gender equality initiatives and help to streamline evaluation. Additionally, evaluation is valuable in understanding the impact that WLPs have as well as the impact they are missing.

This is critical to identifying areas of improvement in existing WLPs, WLPs’ broader role in tackling gender inequalities and women’s continued under-representation in leadership, as well as helping to identify additional policy and legislative change, or other interventions, needed to bring about a desired change.

Contact

You may also like

Calls to address ‘alarming rates’ of gendered violence against Victorian healthcare workers

Our new report finds that gendered violence is widespread in the Australian healthcare system.

The precarity of progress: how traditional gender roles can undermine equality in times of crisis

As the Covid-19 pandemic unfolded, a subtle yet significant shift occurred in homes around the world: the division of household labour became more traditional.

Fixing women or fixing the system?

Australia has made remarkable strides in gender equality in diplomacy, achieving near parity in its Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.